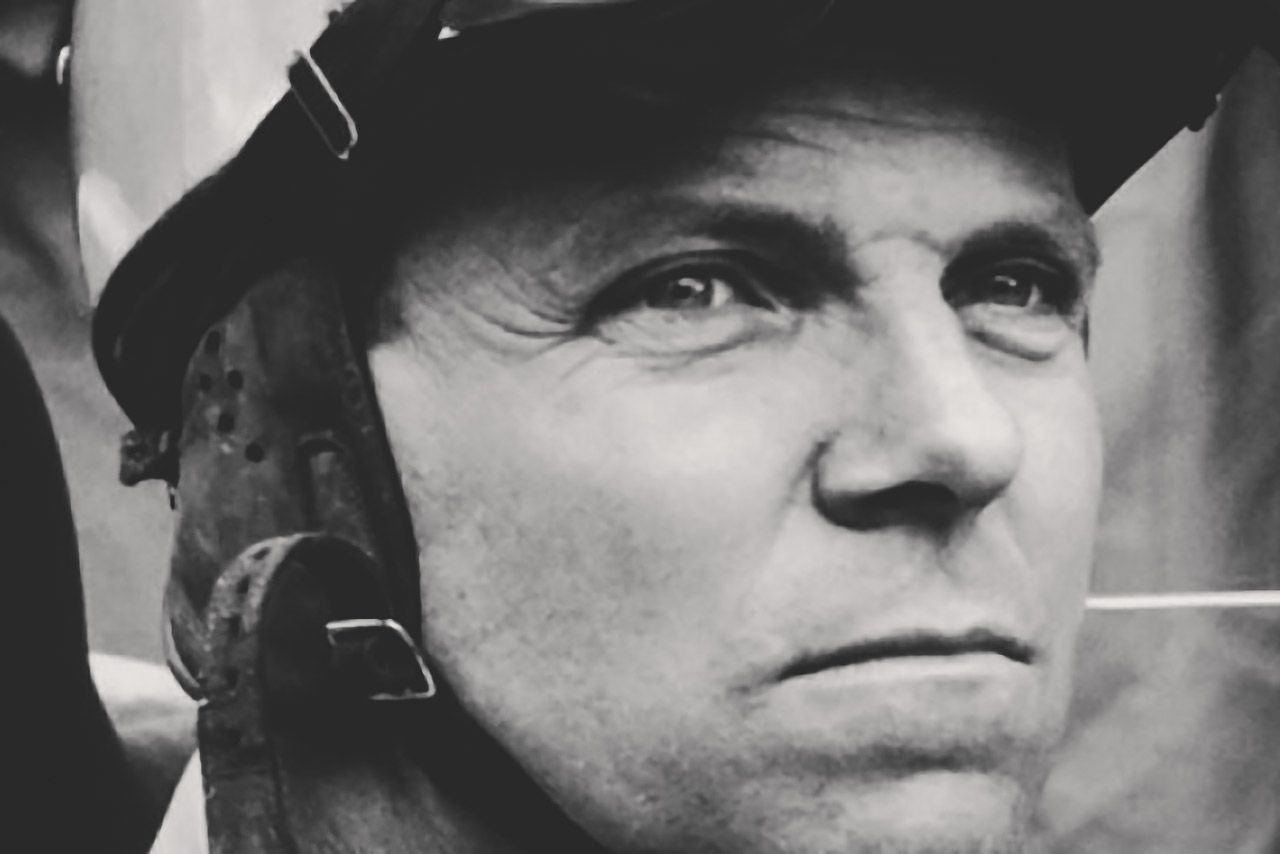

Personality: Paul Frère

Photos: Rob Young Archive / Motorsport Images

Frère had not yet finished his university course in Brussels when he sent what would be his first article to the famous magazine “La Vie Automobile”. The text compared the virtues and limitations of rear and front transmission models. The quality of the work led him to subscribe to the technical section of that publication. It was Frère's first step towards paving the way for a life dedicated to cars, a desire that was born when he accompanied his father, as a spectator, at the 24 Hours of LeMans.

The now journalist's interest in mechanics helped him to have a clearer understanding of how machines work, which made him a potentially good pilot. That was his greatest ambition. Entering motorsport was a necessity and the most economical route would have to be done on two wheels. He became involved locally in motorcycle competitions with considerable success, but his most important result would be victory in the 1948 Brussels Grand Prix, riding a factory Puch 125.

In that environment he established friendships with people linked to motor sport, namely Jacques Ickx, father of the famous driver with the same surname, who is also a renowned journalist in the field. It was on his recommendation that Frère joined the Oldsmobile team in the touring car race in Spa, in class 1, aimed at series production cars. Frère won with some luck and his career was thus launched.

Shortly after, the Belgian was behind the wheel of a Formula 1 HWM, replacing the great Peter Collins in a race in Chimay, who would end up fourth. His performance earned him an invitation from HWM to the Formula 1 Grand Prix, which was held on a very wet Nordschleife circuit, where he would end up beating his teammate, Collins. This was followed by an invitation to the official Porsche team at LeMans and a class victory with the 550 Spyder. In 1954 he received an invitation from Alfred Neubauer to compete in LeMans with the Mercedes 300SL, which, however, were not ready in time. The following year, the invitation was repeated, but Frère had already joined the Aston Martin team with the DB3S and had to refuse. His place behind the wheel of the Gullwing was taken by Pierre Levegh, who was at the origin of the biggest and most famous tragedy in the history of motor sport.

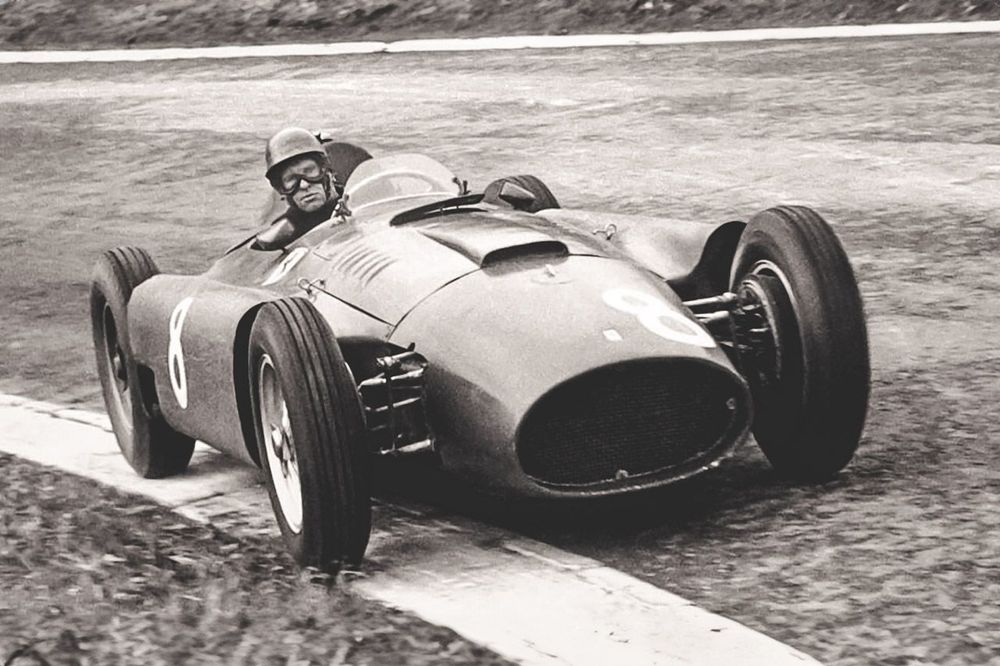

The good performance behind the wheel of the HWM did not go unnoticed by Enzo Ferrari. He would be given the opportunity to drive the 555 Supersqualo. With the Ferrari far below the capabilities of the Mercedes at the time, Paul Frère did practically the best possible in his only official race with the Ferrari: fourth place in the Belgian GP, behind Fangio, Moss and his teammate Nino Farina, plus experienced and familiar with the machine.

Despite this, the driver would no longer compete in the world championship driving a Ferrari. This is because in a Swiss Sport championship race, he had an accident driving a Ferrari Monza, in which he broke his leg and damaged his confidence as a driver. From then on, he decided not to return to Grand Prix cars, the driving of which he found more demanding and dangerous. However, in 1956 an invitation arrived to compete in the Belgian race in 1956, replacing Luigi Musso – who had broken his wrist – at the wheel of the mythical Lancia Ferrari D50. Frère thought the experience would make an excellent journalistic article and so asked to test the car first. After the test it became impossible to refuse, as the potential he saw in the car was incredible. He finished second, behind Peter Collins in a similar car.

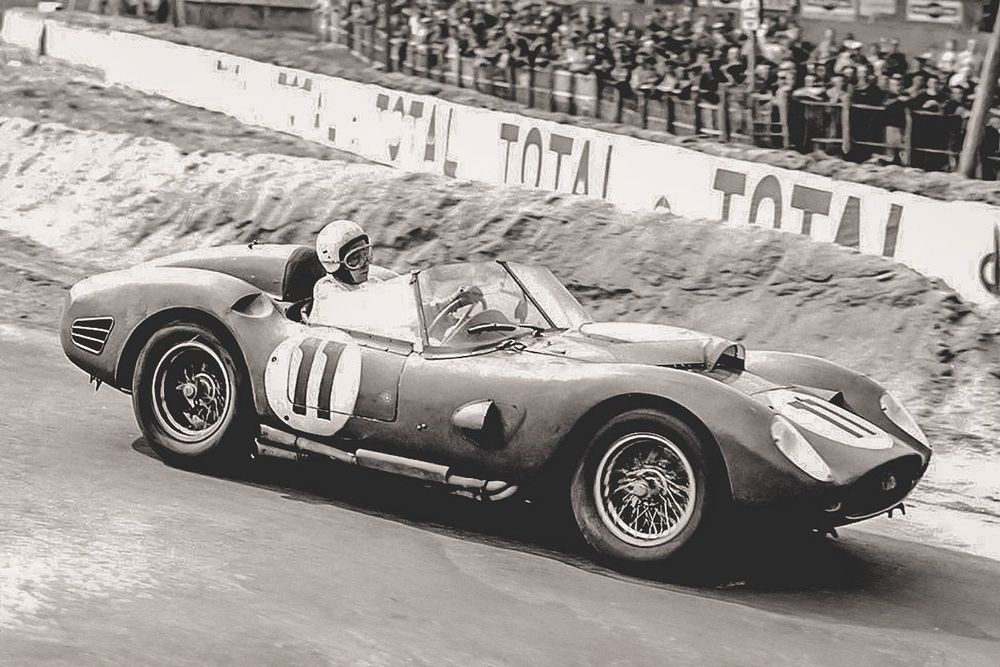

From then on, his career focused on sports cars and had its high point in the victory of the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1960, with Olivier Gendebien in the Ferrari 250 TR59/60.

After proving that he could compete with the big guys on equal terms, he dedicated himself to an extraordinary journalistic career and providing technical consultancy to several manufacturers, especially Porsche.

His autobiographical book “My Life Full of Cars” is a must-read, where you can find one of the most famous phrases: “One day cars will be powered by some alternative energy and, once on the highway, all you have to do is press a button to get from point A to point B. Luckily I won’t live to witness that day.” Unfortunately, the first part is close to being fulfilled and the second came true in 2008, when he passed away at the age of 91. It remains one of the biggest references among automotive journalists.