BX at 40: the last "crazy" Citroën?

Fortunately, I'm not old enough to remember the launch of the Citroën BX, but I grew up in the era in which the model's cultural impact was consolidated. Despite being popular and ubiquitous, the BX looked like nothing else. Few will be able to classify it as beautiful, but that didn't stop it from being a commercial success.

In automobile concept, the BX was not radically different from the GS predecessor. However, it marked a change at Citroën, through a return to Italian design. After Flaminio Bertoni's decisive work in defining the brand's post-war aesthetic identity, Robert Opron signed the new lineage with the SM, GS and CX. The most prominent and prolific designer of the time, Marcello Gandini, was chosen to design the BX.

The designer was not chosen at random, but rather because of his particular style. For this reason, he had the freedom to design the new and most important model in the range with a personal touch, that is, the angular lines. And although there was a certain adaptation to Citroën's stylistic details, the BX's shapes were almost entirely conditioned by Gandini's vision for a family member from the 80s, whatever the brand. Evidence of this lies in the fact that the BX inherited the main features of the proposals previously created by Gandini and seen in the 1977 Reliant FW11 prototype and the Volvo Tundra concept, born with the aim of designing a successor to the 343.

And although the entire design is attributed to him, it is impossible not to identify, especially in the cabin, a stylistic familiarity with the 1980 Citroën Karin concept. The small pyramid-shaped car was designed by Opron's disciple, Trevor Fiore, and his influence is evident, particularly in the instrument panel with integrated buttons, accessible without taking your hands off the steering wheel. An idea that the brand put into practice on Visa and BX.

The Citroën BX arrived on the market in 1982 and, as expected, divided opinions. The straight lines were current, or even somewhat futuristic, and the cabin was unmatched by other rivals. In addition to this, there were the brand's own arguments, with emphasis on the hydropneumatic suspension.

Another asset was its lightness, thanks to some composite panels, namely the fifth door and bonnet.

Launched auspiciously, under the Eiffel Tower, the model marked a turning point in the brand's history for several reasons, mainly because it was the first mid-range model to be launched after the merger with Peugeot. Naturally, the creation of PSA implied the sharing of platforms, components and resources, but even so, the BX had a strong identity and a style that was unmistakably Citroën, albeit in a more "origami" style.

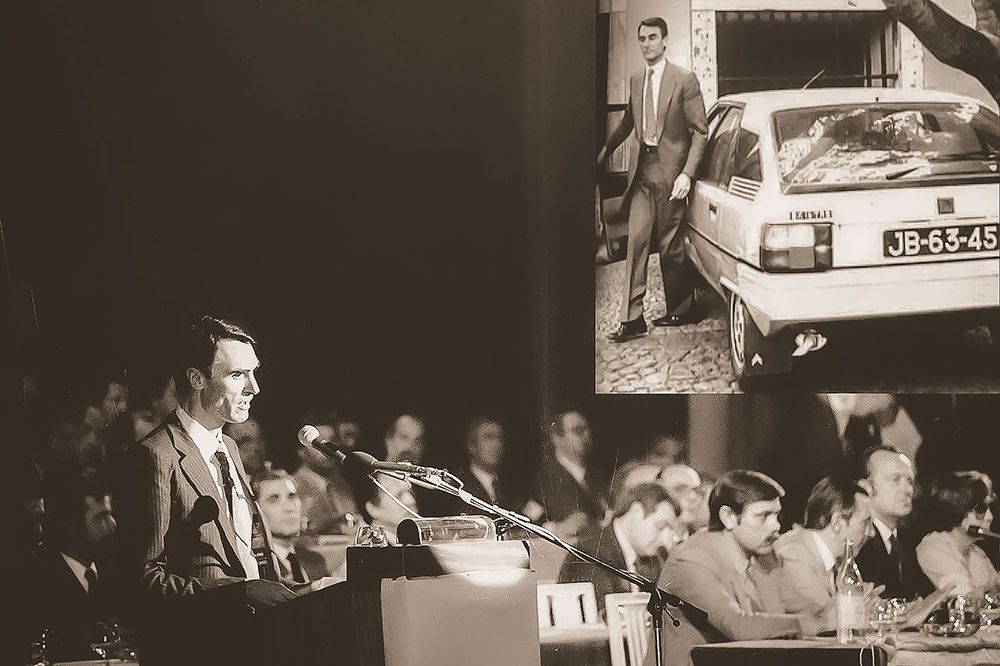

The ability to divide opinions has always been a Citroën characteristic and the BX was no exception. And to further emphasize this controversy, the most famous national owner of a BX would be a politician from Boliqueime, one of the most controversial figures in national politics. The BX 16 TRS, registration JB-63-45 (where is it?), had been acquired by the then professor in March 1985. According to Cavaco Silva himself, on May 19, 1985, the running-in had not yet been completed, as the The way he described his participation in that day's PSD congress went down in history "(...) I had no intention of being elected leader of the PSD when I decided to drive the car to Figueira da Foz".

Today, no one seems to like Cavaco, but in 1985 and throughout the 90s, the electoral results speak for themselves. This perhaps helped to project the idea that the BX was a rational purchase for people of some prestige. What is certain is that many Portuguese people wanted one and, therefore, when the BX 11 arrived on the market in 1990, it was received with great enthusiasm. "Unstoppable at an unbeatable price" was the campaign's headline. Fitting a 1124cc, 55hp engine into a family car, even at the time, seemed absurd. But with a total weight of 900kg, the BX was perhaps the only family member that could get away with so little muscle. The BX 11 could still reach 155km/h and moved quickly enough for the time. The truly unbeatable argument was the price of 1634 cts. To put it into perspective, a Fiat Tipo 1.1 cost 1690 cts., a Ford Escort 1.1 1763 cts. and a VW Golf 1.3 1797 cts. What may seem very little today, in 1990 it was significant, in addition to the fact that the BX looked like a car from a higher segment.

And if a BX with a 1.1 engine may seem absurd, the idea of making it a Group B car seemed even more so, but it ended up happening. The plan led by Guy Verrier (then sporting director at Citroën), consisted of creating a Group B "competition/client" model that private teams could use, similar to what happened with the Visa Trophée and Chrono. This time PSA opted for the model that was important to promote commercially, the BX. When the plan began to be put together, it was already clear that the model would have to have an integral transmission and the initial successes of the Audi Quattro were inspiring for the creation of a front engine layout in a longitudinal position, which would prove to be a huge mistake (until for Audi).

To make matters worse, development costs were so contained that the BX 4TC would be a veritable agglomeration of parts taken from the shelves where mass production models came from: the engine was the N9 TE, 2141cc, it was the same as equipped the Peugeot 505 Turbo and the Matra Murena. The cast iron block used a single camshaft alloy head and Bosch K-Jetronic injection. Supercharging was carried out by a Garrett T3 turbo, helped by an electric compressor that aimed to reduce the gap at lower speeds. In the road version the result was 200 hp, in line with its competitors. In the competition version, the announced 380 hp was meager compared to its rivals. The gearbox used wasn't exactly state-of-the-art, as it was originally from the Citroën SM (the only one in Sochaux's parts inventory capable of handling this level of power). The differentials used at the front and rear were 30% self-locking, but another unpleasant surprise was the lack of a central differential that would allow optimizing torque distribution in difficult grip situations. Thus, the distribution was 50% for each axle, with the particularity of being able to disconnect the rear transmission, thus facilitating maneuvers at low speeds. Speaking of maneuvers, the steering of the BX 4TC is the same as the CX, assisted by the hydropneumatic system and complete with the Diravi system that returns the wheels and steering wheel to their original position.

Another legacy of road cars, this one somehow justifiable for both technical and marketing reasons, is the hydropneumatic suspension. The big advantage is the resistance of the system and the ability to maintain more or less stable ground clearance in all situations and surfaces.

It was relatively easy to guess that the adoption of all these solutions designed and designed for road cars would not translate into extraordinary results in the toughest World Cup qualifiers. In fact, the BX proved to be very ineffective and even less reliable. The Citroën made its debut in 1986. In a season marked by retirements, the BX's best result ever in World Cup competitions was sixth place in the Swedish Rally in the experienced hands of Jean Claude Andruet. That same year, dramatic accidents would occur that would dictate the end of Group B. At this time, Citroën had not yet built all 200 units. According to the BX 4TC register, fed by specialists and owners, a large part of the chassis numbers were reserved for units destined for Guy Verrier's competition-customer program which, never finding enough buyers, never actually got off the ground. Therefore, it is unlikely that 200 BX 4TC were built, especially since most of the units were already built (with improvements and called Evo) in 1987, that is, after the extinction of Group B.

It is known, with certainty, that only 85 units were actually delivered (in a few cases offered, but in the majority sold), although not all of them were registered for road use.

Unfortunately, it wasn't just in rallies that reliability problems arose. Therefore, the warranty costs assumed with customers of the road versions began to increase. Fed up with the nightmare that this project had been, PSA decided to buy back as many units as possible and then dismantle them. This is what happened with 45 examples, meaning that there are only 40 road-going BX 4TC left in the world, although there is uncertainty regarding the whereabouts of some of them, making this the rarest of all Group B models.

Having driven one of the 40 examples, I must confess that the driving experience is as chaotic as the recipe suggests, but even so, I cannot hide my fascination with the model, whether for its history or for the aggressive and irreverent aesthetics of the road version.

But BX's history is not just made up of weaknesses. Models with the 16 TRS, which I remember riding in the 90s, were quite decent in the relationship between performance and comfort and only the parasitic noises took away some refinement from the experience.

For those who know the AX Sport and know how radical that model was, the existence of a BX Sport will seem very strange. In fact, the BX received the same treatment as its "little brother", with Danielson developing the 1905cc engine head, which was now powered by two double carburettors, delivering 126hp at 5800rpm. The suspension was also improved but the behavior would never be as sporty as the rest...

Similar to what happened with the AX, the AX Sport also had as its successor a more civilized BX GTI in three fundamental versions: BX 16 GTI with 115 hp; BX 19 GTI with 125 hp (also available in 4x4) and, finally, the BX 19 GTI 16V with 160 hp. This latest version had very respectable performances. With just 1073kg, I was able to accelerate to 100km/h in 8.5 seconds and reached 217km/h.

In 1989, Citroën decided to distinguish the 16V from the rest of the range with a restyling that was initially proposed in a limited series of 300 units, but would eventually become available in catalogue. The darkened rear lights, the integrated wing and the dark wheels with a gray rim helped to make the difference and made the BX much more "sexy". This version was only available in black, red and pearl and did not have an official name, but thanks to the television advertisement, it was immediately nicknamed the BX "Gandini". An ad that suggested that the Italian designer chose the BX for his everyday car.

The history of the BX was also punctuated by less popular models such as diesels, or the infamous van designed and produced by Heuliez. What is certain is that, over its 12-year career, it would sell 2,315,739 copies. A respectable number, for such a non-consensual model.

The successor would be the Xantia, which was nothing more than a natural successor to the BX, inspired by the lines of the XM, but with half the personality. Citroën would progressively abandon striking features such as Diravi steering or hydropneumatic suspension and would become a manufacturer like the others, just with stranger designs.

The BX was perhaps the last Citroën with great commercial expression to mark the era with its irreverence. Let's toast to that!